Revelle Blog #13 Communicating With Our Instruments

Alec Yates is a Research Assistant at Victoria University of Wellington. He is currently working and reporting on the research occurring along the Hikurangi subduction zone on board the US research vessel Revelle.

Recovery of the electromagnetic instruments has begun, with 9 of 42 recovered from the seafloor at the time of writing this.

The science team are working around the clock, split into a day-shift team (midday to midnight) and a night-shift team (midnight to midday). I am one of the lucky few with the freedom to choose my schedule, so I’ve made the ‘difficult’ decision to stick to somewhat regular hours.

This usually means I am up for the majority of the day-shift, where I can lend an extra hand packing down instruments once they’re onboard. I’m also a useful backup for anyone suffering from sea-sickness which, so far, I’ve managed to avoid!

I thought I’d use this post to describe one stage of the recovery process, the communication between the ship and the instruments on the seafloor.

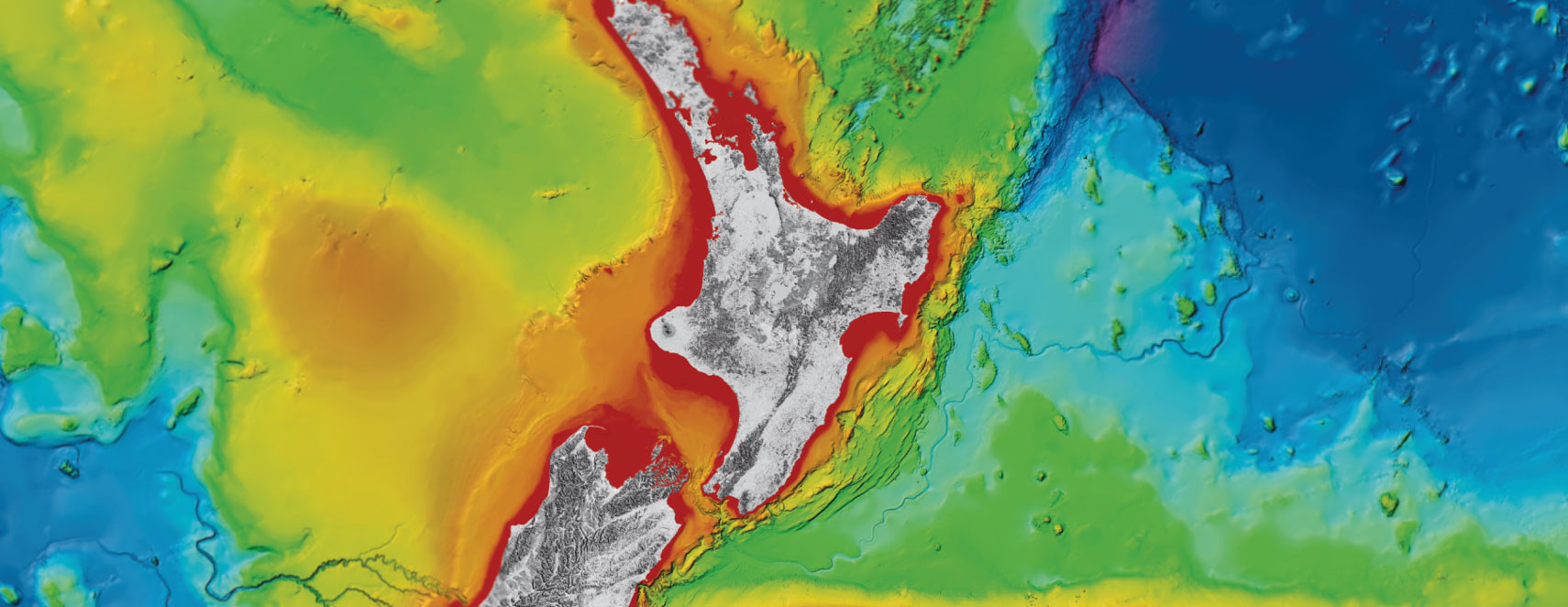

First, when the ship is within a few kilometres of the instrument, we send out an acoustic (sound) signal from the ship at a specific frequency (Part A in figure). The instrument on the seafloor is programmed to detect this signal, listening only for the same frequency as radiated from the ship (11 kHz in this case).

Once detected, the seafloor instrument radiates its own signal at a different frequency to the one emitted by the ship (12 kHz, Part B in figure). The ship, in turn, only listens for this new frequency. This way, we can ensure the ship only detects energy emitted from the instrument, as opposed to any reflections of the energy originally emitted by the ship. Voila, communication is established!

Once we’ve instructed the instrument to release from the seafloor, we wait for confirmation that it has happened as expected. The key is to listen for the number of distinct arrivals of acoustic energy coming from the instrument.

When the instrument is on the seafloor, we only hear one signal returning to the ship, coming directly from the instrument itself. However, when the instrument begins to rise, we are able to hear two distinct signals.

The first occurs as before, coming directly from the instrument (dashed-red line in part C of figure). The second arrival, however, comes from part of the energy reflecting off the seafloor before travelling up to surface (dashed-black line in part C). This only happens when the instrument is no longer on the seafloor, telling us the instrument has been successfully released.

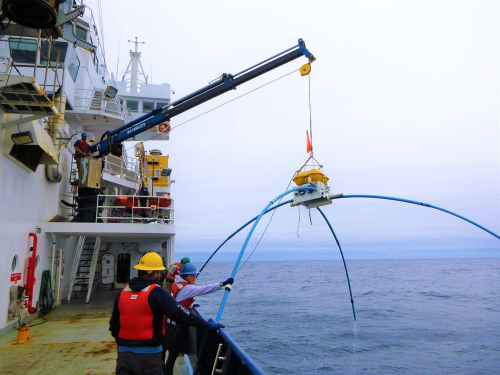

Once that’s done, all we have to do is wait for it to arrive at the surface to then be expertly navigated onboard for deconstruction. See the main image for evidence of such expertise!

Disclaimers and Copyright

While every endeavour has been taken by the East Coast Lab Hikurangi Subduction Zone M9 to ensure that the information on this website is

accurate and up to date, East Coast Lab Hikurangi Subduction Zone M9 shall not be liable for any loss suffered through the use, directly or indirectly, of information on this website. Information contained has been assembled in good faith.

Some of the information available in this site is from the New Zealand Public domain and supplied by relevant

government agencies. East Coast Lab Hikurangi Subduction Zone M9 cannot accept any liability for its accuracy or content.

Portions of the information and material on this site, including data, pages, documents, online

graphics and images are protected by copyright, unless specifically notified to the contrary. Externally sourced

information or material is copyright to the respective provider.

© East Coast Lab Hikurangi Subduction Zone M9 - www.eastcoastlab.org.nz / +64 6 835 9200 / info@eastcoastlab.org.nz